“The Beaver brought paper, portfolio, pens,

And ink in unfailing supplies:

While strange creepy creatures came out of their dens,

And watched with wondering eyes.”

Lewis Carroll, The Hunting of the Snark

Murder in the Court of the Katydid King

by Richard A. Kirk

(Discovered via Phantasmaphile)

Richard A. Kirk’s work will be shown (alongside the work of several other artists) in “Cute and Creepy,” at the Museum of Fine Arts of Florida State University, from October 13th to November 20th. All artwork in this post is his.

The show is described as a show of works combining the Pop Surreal style with an element of the grotesque, “a dissonance of simultaneous attraction and revulsion” (Samantha Levin).

Grotesque being a fascinating word, I will go into it a little further, here. It is a word that has been used to describe the writings of Kafka and O’Connor, and the paintings of Bosch, Goya, and Otto Dix. Nancy Hightower, who teaches Writing and Rhetoric at the University of Colorado, Boulder, says: “What I admire very much about the theory is that it has to play by certain ‘rules’--i.e. just because something is strange and weird, it’s not necessarily grotesque, not in the sense that I teach it. The grotesque is an operation, a form of persuasion that artists and writers use to create a paradigm shift in the viewer. And to me, this shift must always move in the direction of redemption, i.e. in making us a kinder, more loving world.”

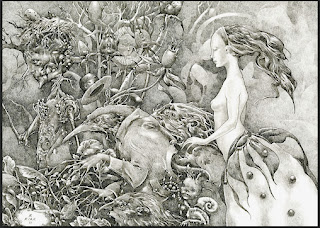

Botanica

By Richard A. Kirk

Hightower’s concept of the grotesque appeals to me in several ways. I am always left cold by art that is merely gross and strange, or art that seems to do nothing but show the gory nature of our society and the painful places we have come to. Art that “mirrors” our daily violence instead of breaking a window or a door out into something better--a surprise, a new idea. A paradigm shift in the direction of redemption--that is something worth our focus.

I have heard this idea before, but never been fully convinced that terrifying aspects really add to the experience of a paradigm shift. Or, I’ve never been too inclined to be fully convinced of it. Her explanation of how the process applies in the works of the “Cute and Creepy” show, though, makes sense: she suggests that by having both humor and horror, both cute and creepy, in front of us, we are moved to a “liminal,” an in-between state, that is, a state where our most solid conceptual and perceptual theories become ungrounded, and a doorway we normally would have been blind to might be noticed. Even opened.

An example is Richard A. Kirk’s “INX”:

The title is a portmanteau, which he unpacks: “The artist and sphinx are combined in a form that suggests a question mark and therefore a riddle. The artist’s hands are brushes, suggesting that he has drawn himself into existence in an effort to find meaning and truth.”

The title is a portmanteau, which he unpacks: “The artist and sphinx are combined in a form that suggests a question mark and therefore a riddle. The artist’s hands are brushes, suggesting that he has drawn himself into existence in an effort to find meaning and truth.”There is a thought: we are all drawing ourselves into existence. An artist (not necessarily a visual artist, either) though, takes that task seriously. He/she is not just throwing together homework at the last minute or riding the treadmill of the punch-clock. Focus. Attention to questions, to riddles. Attempts at teasing them into worlds and possibilities. Kirk is an artist that has honed the fine art of focus: one square inch of an ink and silverpoint drawing will take him about an hour.

There are a lot of things that are scary (thus the creepy part) of not knowing exactly where you’re going. For example, where’s the artist’s next meal coming from? Kirk notes on his (link) webpage that those lured into mysterious other worlds often find trouble.

Promise of the Cuckoo

by Richard A. Kirk

Resistance to integration-- think about a monster in a dream. It is a patchwork of things you are anxious about and afraid of, and things you want to do and the inkling of danger that comes when you try to push forward in your life into something new. Because something new is something unknown, and we just heard Kirk’s warning, an echo of many childhood tales, about what can happen when you follow the strange creature into a mysterious world. That monster is necessary, it’s there to show us how all those things patch together, it’s there not allowing them to blend, so that you can see the distinct pieces, pull it apart, lose your fear, and move forward. Paradigm shift. In studying that monster, you realize why you’re treading water, why you seemingly aren’t able to do the things you think you want to do. Don’t flinch when he breathes fire. Just keep picking at his clothes. It’s only a dream.

In an interview with the creator of Phantasmaphile, Kirk states: “I am interested in liminal things; protean forms. The generation of ideas is both conscious and unconscious. I draw things that I enjoy looking at like birds, insects, trees and books. Over time, I have developed a kind of personal iconography. I try to develop work that tells a story, perhaps not the same story for everyone, but also leaves many questions unanswered. I love mystery in a work of art. Have you read Little, Big by John Crowley? The idea of worlds within worlds interests me very much, like the house Edgewood in the book; a house that inside is many houses.”

The Lost Machine

by Richard A. Kirk

For example, there is the above image. Here is a bird that is mechanical. Someone has to wind it Yet, something else is happening. It eats eggs? Its own young? Or is it caring for its young, carrying it to a safe place? And doesn’t either case make it also alive? Are we the same way, half-wound (by parents, by society, by some god or gods) and half full of our own intentions? Or is this an image that suggests that such a thing as creating our own young is a habit: wind up the human, push it through adolescence (hopefully), toss it out of the nest, and it produces an egg. Are we purely mechanical beings?

And--

inside this image is a novella. So, a story within a story--one with mechanical men, even. Or a series of questions within a series of questions. And it is some sort of mystery novella, to boot, which puts it right up my alley (to be reviewed soon?).

No comments:

Post a Comment