(This is one of a series of stories I am working on that center around a certain, as-yet-unnamed luxury hotel and its inhabitants, both living and haunting.)

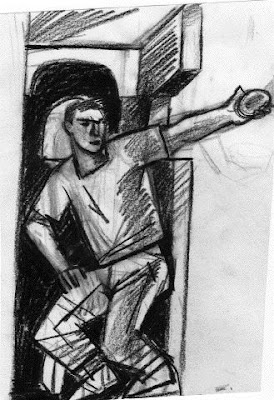

NOTE: All artwork in this post by painter Steve Cieslawski.

Derrick’s pythons developed early in his life, in the elevator shaft of his parents' hotel.

The elevator shafts--there were two--stretched up the sides of the skyscraper like two glass thermometers measuring the wealth of their passengers in degrees. Perfect in every other way, the hotel often had a problem with the elevator on the right, which those outside of the hotel could provide the cause of--if only asked--as they were often offered a clear view of the pale blonde boy scrambling up in the steely morning light. His parents, however, turned a blind eye to this bizarre activity, as almost anything that occupied him at a distance pleased them to no end.

What they didn’t know about were his resultant regular visits to the thirteenth floor.

Unreachable by elevator, the thirteenth floor had been built at only three-quarters height, but in a hotel like this, that still left space to hang from a trapeze. And that was where Derrick had met Jenna’s soul, hanging from a trapeze.

Theater of Memory

(Notice the characters in their performance in her belly...)

Jenna’s soul had occupied the hotel’s 13th floor, along with the souls of several other people, since the explosive street riots of the previous century which had developed soon after a Very Important Politician, in the heady arrogance of new love and imagined moral superiority, had publicly discarded his old Mistress--who had, unfortunately for him and many others, by this time already become a cultural icon. Jenna had the entire story of the city’s rise and fall tattooed on her body. It began on her pinky toe. This is how Derrick would first recognize Jenna’s body later, as an adult and in the outside world: he had spent so long staring at her toes as a boy, toes which would later be enticingly exposed in the expensive pumps she favored. Also, there was her slavish fascination with fashion, which was really just her worldly body’s confused attempt to grasp the color, meaning, and artistic fullness of the tattoos hidden just underneath her skin, on her soul. Her fashion, of course, was always falling short, being the story-less version.

Jenna’s soul’s pinkie-toe was a snow-petal, from the Jissen flower native to the First Mistress’ region. Jissen was also the stage-name of that Mistress, so named for the pale white veils she removed, slowly, over the course of several hours, in an ancient art of dance designed to remove men’s inhibitions in flesh and in pocket. The flower grew only on the highest, snowcapped mountaintop of her family’s region, a mountain whose jealous spirit more often than not burned trespassers with flames of ice and blinding light. Only the poorest of the poor, and only those poor who had been trained since birth to face the difficulties of the search, dared to cross the first skirts of the mountain in search of her flower. And only those chosen by some higher being survived the journey.

Thus the blossoms brought prices higher than any jewel on the market. One blossom, kept planted in its original clay and dampened daily, would live forever. The tears it shed after that daily misting ceremony were collected in small glass jars painted with the likeness of the bloom and sold as perfume to the most elite ladies across the world. If a single petal were to be extracted from the bloom, the rest immediately died, but that one petal, stroked across the skin before it, too, wilted, would remove all wrinkles or other scars of living from the flesh.

Every decade had its claims of Jissen-hunting success.

Jissen the dancer’s flawless, pearly flesh, costly beyond the dreams even of those who were permitted to see her dance, promised life everlasting, but did not belong to her. It belonged to the man who had discovered her. That man, unfortunately for her and many others, was The Politician.

*****

But back to Jenna's soul, and her tattoo.

Flight of the Architect

The petal was hooked by one claw from one long, twiggy leg attached to a long, thin, white bird. The leg was long, but the neck was longer, and the bird twisted and stretched far up the inside of Jenna’s soul’s leg, curling its head down coquettishly at almost the very last minute. It didn’t take up much space, horizontally speaking, but it held its own, attention-wise. Jenna called it Laa Fuba, the Guardian of Long Futures.

“Long, long ago,” she began the tale gravely, turning Derrick’s chin with one light finger to guide his gaze to her eyes, “during previous Dark Times, the End of the World was signaled by the Plague of the Angry Bees.” The bees, looking quite angry indeed, swarmed thickly around her ankle.

“The bees came slowly,” she continued. “The debilitating effects following stings here and there were first thought to be a virus, to which the children especially were susceptible. The children began staying in, which brought hard times for the people, as every hand was needed in most farming tasks.”

She lifted his chin again.

“And then the adults began to fall. They fell in the fields, they fell in the streets, they fell from their chairs at the dinner table. And soon everywhere there was the sound of angry bees, and the streets became filled with the whipping swarms.” She held his eyes with hers. “They heard that sound for many generations in their sleep. For them, the bogey man was a swarm, drawing up from the dust in the darkness.”

“And then the rumors began of the Land of Lakes, the Flatlands, where nothingness stretched forever and ever, interrupted only by nothingness that was reflective and wet. Strange breeds and outlaws lived there, and they were not areas visited much by the people of the farming and town communities. Who even knew how those strange breeds survived, or what threats they might pose?” Jenna paused, looking away, stretching one arm thinly into the air and wrapping it behind her shoulder. She pulled gently on it with her other hand and exhaled, then lifted her body into a backbend and continued with her story, Laa Fuba now flirting with the other side of the hallway:

“The rumors said that in the Land of Lakes, the bees had come and gone and no one had been harmed. Contingencies of men, wrapped in monstrosities concocted of branches and leaves and reeking, bee-repellant saps and animal skins, began journeying into the Flatlands to find the secret that would save their families and their lives. And after many, many weeks and many, many months, long after the ones they’d left behind were certain of their demise along the way, they returned. Carrying eggs.”

Jenna began to crawl, in her backbend, around the hallway. Backwards and forwards, and all around Derrick. Derrick felt his face growing pink. Derrick felt everything growing and pink. After his last visit, he thought he’d never be able to think of anything but toes ever again, yet here he was, developing a fetish for feathers.

“It was the Laa Fuba that saved them. Those long, white, graceful birds of the Flatlands ate the infected bees. They seemed uninterested in regular, every day bees. They ate the sick bees, and the sick bees turned them pink.”

Derrick, thinking she was teasing him, blushed a deeper red.

“And that was all. They turned pink and that was all.” She kicked her legs over, flipping back onto her feet, then sliding her arms between her legs on the ground and squatting to tuck her neck under and curve her back the other way. He stared at the gaping orange lips of a carp gasping at him from the base of her neck.

Jenna reached up for the trapeze and began to twist slowly from a hang. “From then on, in all of the villages, they had breeding farms for the long white bird. And the times of health were called the “Fluttering of Great White Wings,” and they had festivals to honor the bird every year, and the villages and towns were filled with the fluttering of white wings, and one, central float was dedicated to the miraculous pink of their savior.”

Her feet curled and slowly slid up the rope on the right side of the bar. She twisted to a handstand, then let go with her hands, her ankles gripping the rope.

“The float was a giant fuschia boa, its feathers made of silks and cashmeres, panties and socks, everything soft that could be dyed and tied to long and tangled ropes, and they would push the float up the great hill in the center of the village, everyone struggling behind it, and then with one great heave, they pushed it over the top, and the little man-made feathers would flutter wildly in the wind as it sailed back down the other side.” She twisted some more, grasping the opposite rope with her hands then stretching her hands and feet away from each other, curving back, her belly out.

“But even after all that, they still forgot. They still ended up in the Next Dark Times.”

And then she had to quit talking, from exertion.

"Fateful Meeting"

On an older post in this blog, author

Marly Youmans recommended the art of Steve Cieslawski, and I instantly fell in love. I chose his work for this post because of the plethora of liminal spaces like the thirteenth floor in the tale, where one world's arches and floors form the strange sky of another, where a full-color, living head tells stories from a distant, black and white past, and where, incredibly, you can see the flames of the past resolve and settle into the red hair of certain lovely souls gliding through a Sea of Tranquility...the story of the past marking us in very particular, very individual ways, beneath the skin, in the marrow, even changing our DNA...

Philsopher's Twin

Madonna

Sea of Tranquility

"Civilized Discourse"